A nuke explodes in a copper mine under Utah’s Canyonlands as Christian Slater doggedly pursues a cackling mad John Travolta. A white-hot nuclear cloud mushrooms off the coast of the Florida Keys as Jamie Lee Curtis dangles from a helicopter, awaiting rescue by her superspy husband Arnold Schwarzenegger. A 500 (or so) kiloton thermonuclear device is set off in the Ural Mountains as a smokescreen for a lucrative black market deal that Nicole Kidman and George Clooney are then tasked with breaking. Another stolen bomb is dropped on a Baltimore sports arena despite Ben Affleck’s best efforts to stop it.

Since the 1950s, the threat of nuclear war has proliferated among American popular cinema as the ultimate inciting incident, from Fail Safe to Dr. Strangelove, from The Hunt for Red October to Die Hard, acknowledging the do-or-everybody-die nature of war games played with a quiver full of nukes. It’s become such short-hand for dire that this year’s A Good Day to Die Hard doesn’t even bother building a plausible explanation for another mess McClane finds himself in. His CIA-rookie son mumbles a few non sequiturs about uranium-cake stockpiling and Chernobyl. (It’s so preposterously convoluted, in fact, it could be a spoof on the Bush administration’s mendacious cajoling for a coalition of the willing before invading Iraq.)

My conspiracy-theory-prone mind thinks of the links between the CIA Office of Public Affairs and two of last year’s resulting films, Zero Dark Thirty and Argo. Having recently read Tricia Jenkins’s The CIA in Hollywood, I wonder if the Department of Defense has a similar sinister links, links that others might also accept as benign.

B-pictures in the postwar period often used atomic terror to frighten Americans into supporting the United States policy of deterrence. Alfred E. Green’s Invasion U.S.A., the It Could Happen Here for nuclear war, conveys through news reports the horrors that atomic warfare brings yet fails to condemn the use of these weapons. In fact, the entire didactic point is to stockpile stockpile stockpile. The main character complains that he’s not allowed to enlist because the military services lack weaponry. “Soldier’s no good without a gun, a sailor’s no good without a ship.” If only there were more firepower available! (Sounds like the argument the NRA is currently making for guns in schools.)

At the other end of the Hollywood political spectrum, Fail Safe (1964) brought us to the terrifying brink of nuclear holocaust because of an error in the system. A wayward plane sets off a series of automatic “safeties” that lead inevitably to the launching of nuclear missiles. All-out disaster is avoided only because an earnest Henry Fonda sacrifices New York City in exchange for Soviet restraint. The good guys lose, making them seem even better, and the rest of America (and the U.S.S.R.) is spared.

When the Cold War ended, nukes became one way terrorists and supposed rogue nations could menace at the multiplex. But while used as a high-stakes, no-turning-back narrative device, the onscreen implications of actual nuclear explosions are relatively, well, inconsequential.

Healthy butterflies flutter in the wake of the underground explosion in John Woo’s 1996 Broken Arrow, the DOD’s term for a nuclear weapons accident. Slater reassures Samantha Mathis by telling her if the butterflies can make it, so will they. No one’s skin even gets singed in the big blast at the end of True Lies (1994) and Affleck’s future wife emerges beautifully alive after the explosion in The Sum of All Fears (2002), even as she’s a surgical resident at a hospital near the blast zone. In Mimi Leder’s The Peacemaker (1997), a nuclear bomb poignantly (if action-packed has room for poignancy) kills an elderly caretaker couple whom we meet only for an instant, but the fallout is as minimal as the concern. To Leder’s credit, the purloined bomb headed for Manhattan is treated as dire (it never goes off) but only because it would impact Terra americanus. The people, flora, fauna, and ground water of the Urals, oh well. Our swimming pool water is still radiation free!

My childhood memories are papered over with the imagery of the Cold War era, including the ridiculous duck-and-cover instructions given in elementary school. An adulthood lived in the shadow of the apparently never-ending War on Terror, I now worry alongside the rest of America about the specter of a dirty bomb that the Cheney cabal conjured during those eight long years to scare the dissent out of us. I’ve also worried that recent depictions of the consequences of nuclear are too glib and might accumulate into a creeping acceptance of the inevitability of a nuclear war, a manufactured consent that could send missiles flying over to North Korea or Iran, really, any day now. In the same way that cop shows erode the average citizen’s understanding of their rights. Just watch any episode of the Special Victims Unit of the Law and Order franchise—the guilty don’t deserve them; the innocent don’t need them. The Japanese of Nagasaki and Hiroshima have yet to have their Shoah or Schindler’s List, image-based stories that stick in the public’s consciousness.

On the other hand, with all the gun-toting heroes and villains that populate the films we see, the majority of the moviegoing public seem to grasp the idea that shooting others is bad. They don’t it—or do—knowing the horrible consequences, maybe even a little because of the movies. Considering the number of nukes around, it’s a wonder they don’t “go off” more often. Not that we have any control over why or when the button gets pushed. In a recent Scientific American article about what really ended World War II, the author compares the nuclear arsenal to a T-Rex: “[O]ne could possibly imagine a use for such a creature in extreme situations, but by and large it only serves as an unduly sensitive and enormously destructive creature whose powers are waiting to be unleashed on to the world. Having the beast around is just not worth its supposed benefits anymore, especially when most of these benefits are only perceived and have been extrapolated from a sample size of one.”

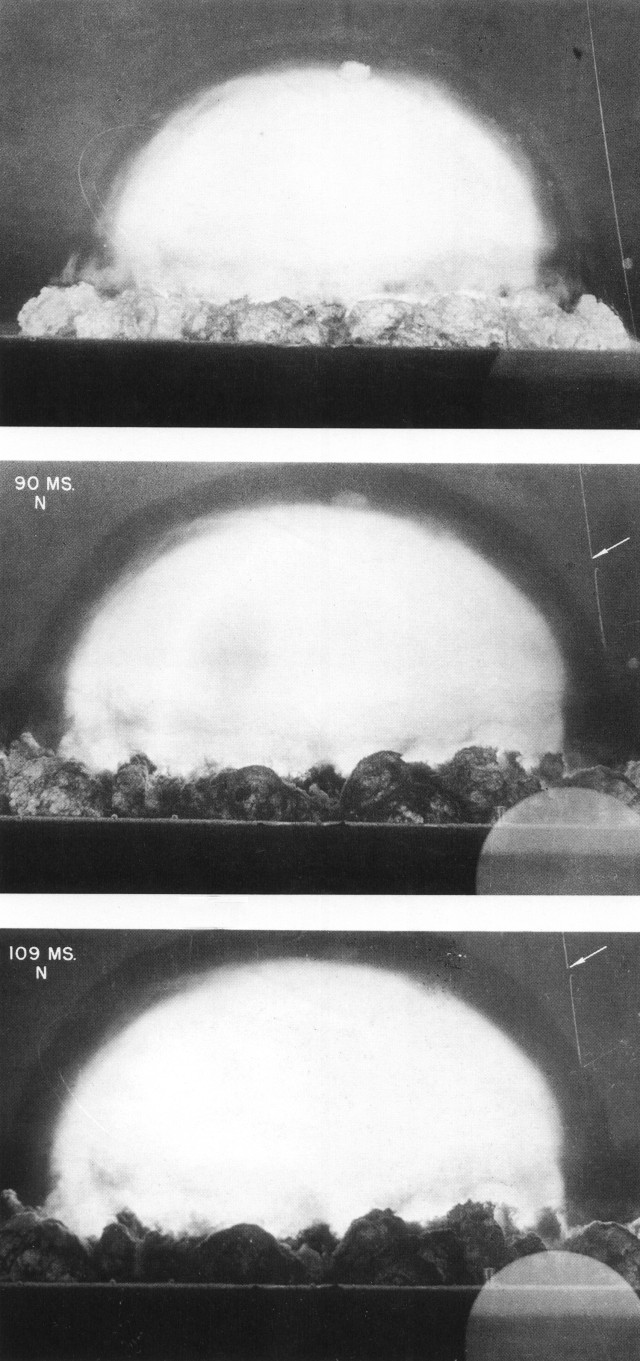

Maybe I worry too much. Documentaries abound and give us ample warning. Jon Else’s 1980 The Day After Trinity reveals Oppenheimer’s change of heart about building atomic weapons. Peter Kuran’s Trinity and Beyond (1995) uses previously classified films shot of nuclear tests, atomic to thermonuclear, Trinity to Castle Bravo, simultaneously showing the awesome power of these weapons and their incongruously photogenic qualities. Atomic Wounds (2006) documents the long-term effects of the bomb’s fallout through the eyes of a doctor who helped victims on August 6, 1945, and still tends to the Hibakusha (survivors of the bombings) today.

Besides, other special effects aren’t accompanied by disclaimers. No “Don’t Try This At Home” warnings precede a scene of Jackie Chan jumping off a downtown building onto a storefront awning. The consequences of regular bombs exploding have even been played for laughs as far back as movies have been made. See the comical aftermath of a “conventional” bomb going off in Buster Keaton’s Cops (1922). (One stand-out actor is hilariously zombie-like in tattered clothes.) We can laugh at it and still take that threat seriously. Try to say the word “bomb” at an airport, before or after September 11th, 2001.

Still, I wish more films that reach a wide audience had the cautionary effect Dr. Strangelove’s dark humor or even marginal fare like John Carpenter’s 1974 Dark Star, a low-budget spoof of both Strangelove and 2001. A four-man crew trolls the universe in their spaceship toting an arsenal of nuclear bombs, destroying unstable planets, making space safe for colonization. Their sole stated purpose is to blow shit up. After they manage, for the third time, to dissuade bomb #20 from automatically detonating, one crew member sighs with enormous relief and says, “You know we really gotta disarm the bomb.” No one ever does.

— Shari Kizirian © 2013

Originally published with clips on Keyframe, Fandor’s daily cinema blog in April 2013